A Whirlwind Tour of the Kotlin Type Hierarchy

Kotlin has plenty of good language documentation and tutorials. But I’ve not found an article that describes in one place how Kotlin’s type hierarchy fits together. That’s a shame, because I find it to be really neat1.

Kotlin’s type hierarchy has very few rules to learn. Those rules combine together consistently and predictably. Thanks to those rules, Kotlin can provide useful, user extensible language features – null safety, polymorphism, and unreachable code analysis – without resorting to special cases and ad-hoc checks in the compiler and IDE.

Starting from the Top

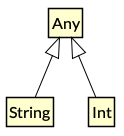

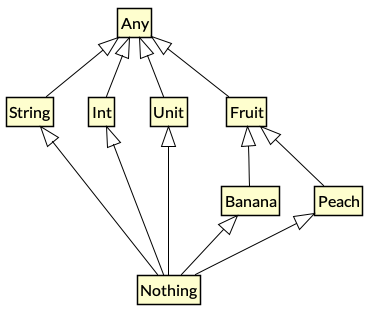

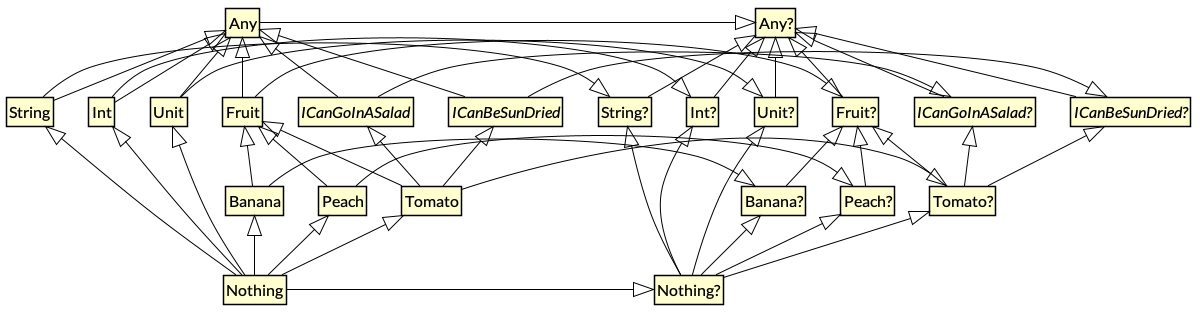

All types of Kotlin object are organised into a hierarchy of subtype/supertype relationships.

At the “top” of that hierarchy is the abstract class Any. For example, the types String and Int are both subtypes of Any.

Any is the equivalent of Java’s Object class. Unlike Java, Kotlin does not draw a distinction between “primitive” types, that are intrinsic to the language, and user-defined types. They are all part of the same type hierarchy.

If you define a class that is not explicitly derived from another class, the class will be an immediate subtype of Any.

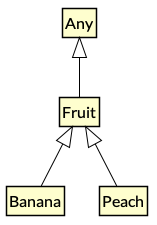

class Fruit(val ripeness: Double)

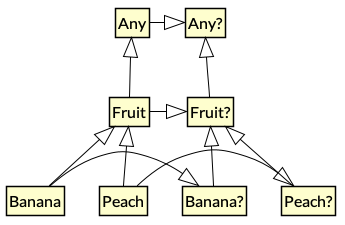

If you do specify a base class for a user-defined class, the base class will be the immediate supertype of the new class, but the ultimate ancestor of the class will be the type Any.

abstract class Fruit(val ripeness: Double)

class Banana(ripeness: Double, val bendiness: Double):

Fruit(ripeness)

class Peach(ripeness: Double, val fuzziness: Double):

Fruit(ripeness)

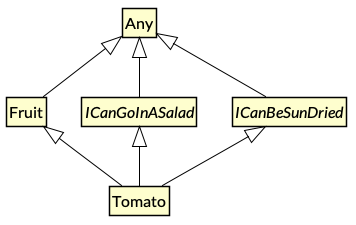

If your class implements one or more interfaces, it will have multiple immediate supertypes, with Any as the ultimate ancestor.

interface ICanGoInASalad

interface ICanBeSunDried

class Tomato(ripeness: Double):

Fruit(ripeness),

ICanGoInASalad,

ICanBeSunDried

The Kotlin type checker enforces subtype/supertype relationships.

For example, you can store a subtype into a supertype variable:

var f: Fruit = Banana(bendiness=0.5)

f = Peach(fuzziness=0.8)But you cannot store a supertype value into a subtype variable:

val b = Banana(bendiness=0.5)

val f: Fruit = b

val b2: Banana = f

// Error: Type mismatch: inferred type is Fruit but Banana was expected Nullable Types

Unlike Java, Kotlin distinguishes between “non-null” and “nullable” types. The types we’ve seen so far are all “non-null”. Kotlin does not allow null to be used as a value of these types. You’re guaranteed that dereferencing a reference to a value of a “non-null” type will never throw a NullPointerException.

The type checker rejects code that tries to use null or a nullable type where a non-null type is expected.

For example:

var s : String = null

// Error: Null can not be a value of a non-null type StringIf you want a value to maybe be null, you need to use the nullable equivalent of the value type, denoted by the suffix ‘?’. For example, the type String? is the nullable equivalent String, and so allows all String values plus null.

var s : String? = null

s = "foo"

s = null

s = barThe type checker ensures that you never use a nullable value without having first tested that it is not null. Kotlin provides operators to make working with nullable types more convenient. See the Null Safety section of the Kotlin language reference for examples.

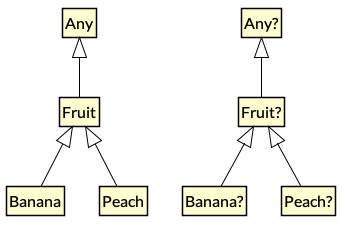

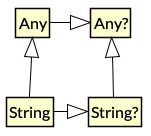

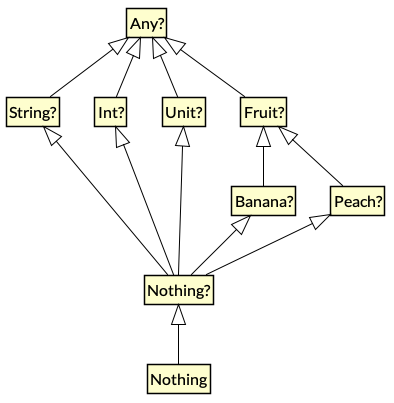

When non-null types are related by subtyping, their nullable equivalents are also related in the same way. For example, because String is a subtype of Any, String? is a subtype of Any?, and because Banana is a subtype of Fruit, Banana? is a subtype of Fruit?.

Just as Any is the root of the non-null type hierarchy, Any? is the root of the nullable type hierarchy. Because Any? is the supertype of Any, Any? is the very top of Kotlin’s type hierarchy.

A non-null type is a subtype of its nullable equivalent. For example, String, as well as being a subtype of Any, is also a subtype of String?.

This is why you can store a non-null String value into a nullable String? variable, but you cannot store a nullable String? value into a non-null String variable. Kotlin’s null safety is not enforced by special rules, but is an outcome of the same subtype/supertype rules that apply between non-null types.

This applies to user-defined type hierarchies as well.

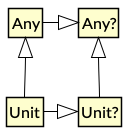

Unit

Kotlin is an expression oriented language. All control flow statements (apart from variable assignment, unusually) are expressions. Kotlin does not have void functions, like Java and C. Functions always return a value. Functions that don’t actually calculate anything – being called for their side effect, for example – return Unit, a type that has a single value, also called Unit.

Most of the time you don’t need to explicitly specify Unit as a return type or return Unit from functions. If you write a function with a block body and do not specify the result type, the compiler will treat it as a Unit function. If you write a single-expression function, the compiler can infer the Unit return type, just like any other type.

fun example1() {

println("block body and no explicit return type, so returns Unit")

}

val u1: Unit = example1()

fun example2() =

println("single-expression function for which the compiler infers the return type as Unit")

val u2: Unit = example2()There’s nothing special about Unit. Like any other type, it’s a subtype of Any. It can be made nullable, so is a subtype of Unit?, which is a subtype of Any?.

The type Unit? is a strange little edge case, a result of the consistency of Kotlin’s type system. It has only two members: the Unit value and null. I’ve never found a need to use it explicitly, but the fact that there is no special case for “void” in the type system makes it much easier to treat all kinds of functions generically.

Nothing

At the very bottom of the Kotlin type hierarchy is the type Nothing.

As its name suggests, Nothing is a type that has no instances. An expression of type Nothing does not result in a value.

Note the distinction between Unit and Nothing. Evaluation of an expression type Unit results in the singleton value Unit. Evaluation of an expression of type Nothing never returns at all.

This means that any code following an expression of type Nothing is unreachable. The compiler and IDE will warn you about such unreachable code.

What kinds of expression evaluate to Nothing? Those that perform control flow.

For example, the throw keyword interrupts the calculation of an expression and throws an exception out of the enclosing function. A throw is therefore an expression of type Nothing.

By having Nothing as a subtype of every other type, the type system allows any expression in the program to actually fail to calculate a value. This models real world eventualities, such as the JVM running out of memory while calculating an expression, or someone pulling out the computer’s power plug. It also means that we can throw exceptions from within any expression.

fun formatCell(value: Double): String =

if (value.isNaN())

throw IllegalArgumentException("$value is not a number")

else

value.toString()It may come as a surprise to learn that the return statement has the type Nothing. Return is a control flow statement that immediately returns a value from the enclosing function, interrupting the evaluation of any expression of which it is a part.

fun formatCellRounded(value: Double): String =

val rounded: Long = if (value.isNaN()) return "#ERROR" else Math.round(value)

rounded.toString()A function that enters an infinite loop or kills the current process has a result type of Nothing. For example, the Kotlin standard library declares the exitProcess function as:

fun exitProcess(status: Int): NothingIf you write your own function that returns Nothing, the compiler will check for unreachable code after a call to your function just as it does with built-in control flow statements.

inline fun forever(action: ()->Unit): Nothing {

while(true) action()

}

fun example() {

forever {

println("doing...")

}

println("done") // Warning: Unreachable code

}Like null safety, unreachable code analysis is not implemented by ad-hoc, special-case checks in the IDE and compiler, as it has to be in Java. It’s a function of the type system.

Nullable Nothing?

Nothing, like any other type, can be made nullable, giving the type Nothing?. Nothing? can only contain one value: null. In fact, Nothing? is the type of null.

Nothing? is the ultimate subtype of all nullable types, which lets the value null be used as a value of any nullable type.

Conclusion

When you consider it all at once, Kotlin’s entire type hierarchy can feel quite complicated.

But never fear!

I hope this article has demonstrated that Kotlin has a simple and consistent type system. There are few rules to learn: a hierarchy of supertype/subtype relationships with Any? at the top and Nothing at the bottom, and subtype relationships between non-null and nullable types. That’s it. There are no special cases. Useful language features like null safety, object-oriented polymorphism, and unreachable code analysis all result from these simple, predictable rules. Thanks to this consistency, Kotlin’s type checker is a powerful tool that helps you write concise, correct programs.

“Neat” meaning “done with or demonstrating skill or efficiency”, rather than the Kevin Costner backstage at a Madonna show sense of the word↩︎